Quarries

Mont Mado has played an important role in Jersey's building industry over the centuries, first as an area where stone was quarried for use in construction from prehistoric days to the 20th century; then as a hole in the ground to be filled with rubble from building sites to make way for further development.

The quarries were once the most famous on the island, producing the finest granite in a range of colours from pink to bright red.

The name

Although the name sounds as if it should be of French origin, the 'Mado' is believed to derive from Fief Madoc, which researchers suggest may in turn derive from the Welsh prince, Madoc (Madog) ab Owain Gwynedd, who is reputed to have sailed to America in 1170, although how his name could have become attached to an area of St John in Jersey cannot be explained. There is a reference in the 1331 Extente of Edward III to the purchase of 3 bouvées of land in Fief Madoc by Colin Le Maignen.

La Hougue Bie

The area around Mont Mado was renowned for its quality stone over 5,000 years ago. A good example can be seen at La Hougue Bie in Grouville. This ancient passage tomb was constructed of granite from a number of different locations in the island, including Mount Bingham. Archaeologists have found only two pieces of Mont Mado granite on the whole site and these were saved for the most sacred parts of the structure.

The orthostat is the stone at the heart of the tomb. It is aligned to catch the first rays of the sun on the day of the equinox. Underneath the orthostat is a quern or grinding stone. Both are made from Mont Mado granite.

The Neolithic quarrymen of Mont Mado valued this stone very highly as they took a great deal of trouble and effort to prepare it and transport it from Mont Mado to La Hougue Bie.

Two possible methods of splitting stone were to heat it and then pour cold water over it, or to drive in wedges of wood and then to soak them so that they expanded. Once the quarrymen had a usable rock they had to roll it, drag it or push it to where it was needed. In this case the rocks were rolled several miles to La Hougue Bie.

Commercial quarrying

During the following centuries Mont Mado granite was used on a relatively small scale as a building stone for houses in Jersey from the grandest buildings to solid farmhouses and simple cottages and sheds. However, the earliest apparent reference to quarrying being carried out on a commercial scale is a Royal Court document from 1684 regarding the transport of stones from Mont Madoc, or Madoe Quarry, to Moulin de Malassis, of which the tenant was Jean de la Cloche. The document also names Richard Falle, Pierre Poingdestre and Jean Hubert, Chefs de Charette of the Fief du Roi in St Saviour.

Copenhagen Harbour

Mont Mado granite was not exported in large quantities but it was used for one particular overseas building project - the harbour at Copenhagen.

The quarries at Mont Mado did not have a single overall owner during the 19th century. Various parts of the land and quarries in the area belonged principally to the Sarre and de Gruchy families. Charles de Gruchy, with partners Richard Queree and Josue Renouf, purchased part of the quarries from Helier Sarre in 1872. Charles was later to buy out his partners in 1882.

Charles retired in the 1890s and left the running of the quarry to his son-in-law Joseph Le Seelleur. However he could not resist coming back to the quarry to check on the work and to join in. On the last occasion he visited he helped to set a jig in place, which was to lift a huge boulder. The jig collapsed and flying debris killed him. The subsequent inquest discussed the safety implications of standing under a huge boulder while it was being lifted.

Census figures

The quarries and granite trades provided a huge amount of employment in the Mont Mado area. The 1851 census for St John records that there were 2 masons, 13 quarrymen, 6 stone dressers and a stone merchant living and working in the area. There were also at least 3 master quarrymen employing their own labour who were resident around the quarry.

William Adair was a Mont Mado quarryman. In 1861 he is listed as living with his wife and four children. The oldest child George, aged 14, had followed his father to the quarry and was working as a stone cutter.

William was born in Malta but came to Jersey and married a local girl. The census shows that in addition to their own children the Adairs also had care of Michael Temple aged 6 who was not their natural son.

A Mr Middleton had found Michael on a doorstep of 8, Temple Place, St Helier [St Marks Road] at 8pm on the night of the 15th of December 1854. Hospital records show that he was aged about 3 days at the time.

He was boarded with the Adair family and they later appear to have adopted him as he is recorded on the 1871 census as their adopted son. Michael later changed his name to Adair keeping the Temple as a middle name. Michael stayed with the family in Mont Mado until he was an adult and trained as a shoemaker. After he married and had his own family he became one of the first postmen in St John.

The Le Quesne Family became the owners of the quarries in the early 20th century. Charles Thomas Le Quesne first inherited part of the property from his father who had purchased it from Charles de Gruchy in 1907 and then purchased the rest of the property from Josué Sarre in 1931. By 1933 the company Charles Le Quesne Limited had taken over the quarries and they were sold to the States of Jersey in 1958.

Windmill

On the top of the quarry there once stood a windmill, like the quarry it no longer exists, but through records held at Jersey Archive we can trace the history of this structure.

Fire insurance registers show that the windmill was constructed of stone with wooden cladding. The registers also record that it was a wind corn mill used to produce flour for domestic purposes. The windmill stood over 400 feet above sea level and it was known as a navigation point for shipping.

The windmill was built between 1826 and 1827. Contracts show that George Ourry Lempriere, Seigneur of the Fief Chesnel leased land to Jeanneton Simon in August 1826 giving her a year and day to build the structure. The lease on the property ran until 1886. Construction was partly financed by selling promissory bank notes with a picture of the windmill on them.

In 1827 Jeanneton Simon leased out half the windmill to Jean de la Cour and in 1828 the other half to Joseph Le Brun with both leases running until 1886 - the length of Jeanneton’s original lease with the Seigneur.

Unfortunately in 1837 she was subject to bankruptcy proceedings – known locally as décret. The windmill continued to be leased until 1853 when Joseph Philippe Le Brun, the son of the original Joseph, ceded all rights and lifetime enjoyment back to François Godfray the Seigneur of Fief Chesnel thus completing the circle.

Sadly only 50 years after the windmill was built it was already falling into ruin. The cliff that was quarried below it created a strong updraft that destroyed the sails. For a while the windmill was used to pump water from the quarry but eventually it fell into disrepair and was reported to be in a sorry state just before the First World War. Evidence is hard to find for the eventual collapse of the windmill but we know that it no longer existed by the 1930s.

Priory

The quarry and windmill are not the only significant landmarks to have been located in the Mont Mado area. Near the site of the quarry there once stood a priory or religious house known as the Chapel of St Blaize and later St Blaize and St Marguerite.

Little is known about the chapel, although it is mentioned in early ecclesiastical lists. Richard Le Hardy son of former Bailiff Clement Le Hardy was named chaplain of the of St Blaize and Marguerite on the 25th of May 1507. We can only surmise that it probably fell victim to the reformation some time after the 1520s.

There is still some evidence of the chapel’s existence in the Mont Mado area. The house St Blaize is reputed to have parts of the chapel embedded in its walls and a second house, La Porte is also supposed to have connections with this ancient priory.

Gallery

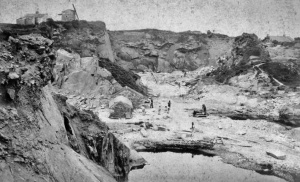

1872 Photograph by Ernest Baudoux

1872 photograph by Ernest Baudoux